This video has been made available by the North Carolina Bar Association and Legal Aid of North Carolina as a public service. This video is for general informational purposes only and is designed for people who cannot afford to hire a private attorney to address their custody issues. The North Carolina Bar Association and Legal Aid of North Carolina make no assurances that this video will enable you to succeed in resolving your custody matter. The information provided in the video is general legal information and is not legal advice. Legal advice is dependent on the specific circumstances of each situation. The information contained in this video is not guaranteed and the information contained in the packet cannot replace the advice of a competent attorney licensed in your state. It does not imply that the North Carolina Bar Association or Legal Aid of North Carolina has agreed to represent you or provide you with further advice or counsel. No one from Legal Aid or the North Carolina Bar Association will appear on your behalf in court. In no event will the North Carolina Bar Association or Legal Aid of North Carolina or anyone contributing to the production of this video be held responsible for any damage resulting from the use of the video. This video is meant to assist parents who are preparing for a custody trial in North Carolina courts. Laws vary from state to state, so if you are not located in North Carolina or you are not a biological or adoptive parent of the child you are seeking custody of, the information in this video may not apply to your custody case. If you have any questions about how to prepare for your custody trial or how to present your case, please consult with a competent domestic attorney...

Award-winning PDF software

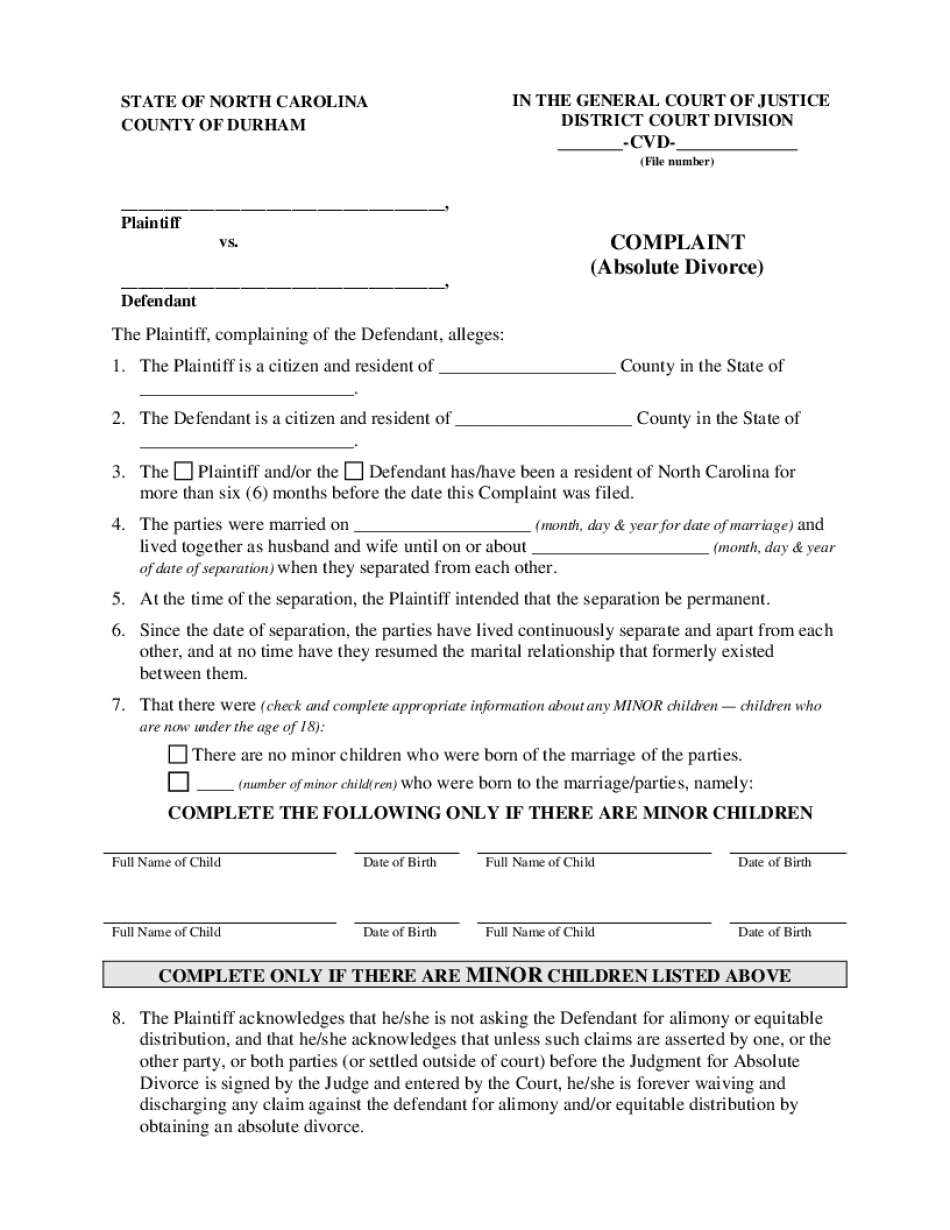

North carolina divorce court Form: What You Should Know

Read this article that describes the process. How to Write a Simple Divorce with Court Forms How to Write a Simple Divorce Using the Self-Help Program from South Carolina Legal Services Self-Help Program Basics South Carolina Legal Services. This online self-help program is not available in all areas — please call our offices or stop by to see if this service is available in your area. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for South Carolina residents who cannot easily attend an attorney's office for a self-help program. We have a wide range of programs which can be ordered online. Please check often back for program updates. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for those who cannot write a standard letter of divorce. Our letters of divorce are not typed; instead we use our interactive program. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for those with an attorney, but cannot attend the attorney's office for a self-help program. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for those wishing only to use an online self-help program, rather than go to an attorney for a letter of divorce. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for those with no internet access. South Carolina Legal Services. This self-help program provides a self-help program for those who cannot write a traditional self-help procedure.

online solutions help you to manage your record administration along with raise the efficiency of the workflows. Stick to the fast guide to do NC Court Form Complaint absolute Divorce, steer clear of blunders along with furnish it in a timely manner:

How to complete any NC Court Form Complaint absolute Divorce online: - On the site with all the document, click on Begin immediately along with complete for the editor.

- Use your indications to submit established track record areas.

- Add your own info and speak to data.

- Make sure that you enter correct details and numbers throughout suitable areas.

- Very carefully confirm the content of the form as well as grammar along with punctuational.

- Navigate to Support area when you have questions or perhaps handle our assistance team.

- Place an electronic digital unique in your NC Court Form Complaint absolute Divorce by using Sign Device.

- After the form is fully gone, media Completed.

- Deliver the particular prepared document by way of electronic mail or facsimile, art print it out or perhaps reduce the gadget.

PDF editor permits you to help make changes to your NC Court Form Complaint absolute Divorce from the internet connected gadget, personalize it based on your requirements, indicator this in electronic format and also disperse differently.

Video instructions and help with filling out and completing North carolina divorce court